Her composure was wilting. Her voice quivering. Her will breaking. Fast.

My wife began to cry as she spoke to a 911 dispatcher. She was angry. Frustrated. Losing hope.

We were cold. Tired. Trapped.

The snow was quickly building around us, and there was nothing we could do about it.

I tried to console her. Explain to her that remaining calm was our best plan of action — our only plan of action. But her voice continued to rise.

What an end to a honeymoon. We had spent the last handful of days on the beach, in the sun, under a cloudless sky. Now this!

We had planned to delay our honeymoon from after our wedding in August for this very reason. A short reprieve from the cold winds of November sure would be nice, we thought.

It was.

But we weren’t expecting to return to this. We had never seen so much snow.

Few have.

—

We began our ascension from Punta Cana International Airport aboard U.S. Airways flight 1966 at 3:50 p.m. on Monday, November 17, 2014. Our expected arrival in Buffalo was 9:54 p.m. following a 1 hour, 49 minute layover in Charlotte.

We hoped to be at our Olean home and in bed by 1 a.m. at the latest following the 75-mile drive from Buffalo. We were looking forward to being back after a week away.

The flight from Punta Cana to Charlotte was smooth. We arrived around 6:30 p.m. with our next flight expected to depart at 8:15.

We grabbed a quick a dinner and sought to find our boarding gate. We were greeted with ominous news. This is when our trip slowly began to unravel.

A A319, 124-seat Airbus was standing idle at the gate, but a crew to man the plan was nowhere to be found. They were delayed. When they might arrive was unknown. There was a chance our flight might be postponed until the morning.

We were upset. We were exhausted. We were ready to be home.

We quietly stewed at the thought of having to spend the night where we sat. Looking back, we would have gladly accepted a night – or two – sleeping on the carpeted floors of Charlotte Douglas International Airport.

—

An applause filled the gate area. Weary travelers breathed a sigh of relief. The crew had arrived. We were going home.

We ascended from the runway shortly after 10 p.m. Now, we were only left with one concern: what kind of weather would welcome us in Buffalo.

During a phone conversation with my dad while in Charlotte, he warned that a winter storm was coming. He implored us to be careful.

The warning, the words, were familiar. We were accustomed to living in and maneuvering through and around the snow. We would be fine, I thought.

I had driven in all manners of snow since age 16. We might have to take it slow, but we would make it home intact.

As we descended upon Buffalo after a bumpy flight that caused my wife stomach discomfort, a flight attendant came over the loud speaker to provide a weather update.

All was clear!

By now, Monday, November 17 had turned to Tuesday, November 18.

—

I couldn’t see where I was going. We were afraid of what was ahead. We were afraid of losing control.

Just five miles into our journey, all hell broke loose. Travelling south on Transit Road, outside Buffalo, we drove into a stiff curtain of giant snowflakes. Illuminated by our headlights, that was all we could see. All around us.

Unable to see even a foot beyond the front bumper, I begrudgingly steered my wife’s Kia Sorento into an empty AutoZone parking lot. Panic had begun to set in.

“What should I do?” I asked in frustration

My wife didn’t have an answer.

Part of me wanted to wait five or 10 minutes for the snow to let up. A bigger part of wanted to continue.

As snow continued to pile up around us, I maneuvered the small SUV out of the lot and onto the main road again. If it were possible, the snow was now coming down faster and with more fury.

Less than a mile later, I had lost all vision of the road. I had to pull to the side. Now!

I spotted what appeared to be a parking lot and attempted to turn in. Our tires met a mound of snow. The vehicle stopped cold, barely off the road.

Before we could begin to establish a plan B, a snow plow approached from behind and buried us further. We wouldn’t be moving any time soon.

—

We felt relieved.

A tow truck was on its way to save us. We would get back on the road and find a hotel for the night. We would be home the next morning.

Then the phone call came. It was Triple A. It would be a few hours before they could help us. The snow was heavy, they said. There were others in line ahead of us.

So we hunkered down and tried to stay warm. It was almost 2 a.m.

Snow continued to fall furiously. It built around us. There were no signs of it letting up.

I turned off the engine, wary that tail pipe had already become engulfed in snow. Worried that we’d be trapped in the car by the rising snow, my wife pushed me to venture outside every so often and remove the piles surrounding the four doors.

I was wearing sneakers and a windbreaker. So was my wife. We didn’t have winter hats, gloves or scarves. When we had left Olean for Buffalo on November 10, the weather was mild. The temperatures were in the 40s and 50s. We were expecting similar on our return.

We were unprepared for any snow, never mind feet of it. My socks become cold and wet. My feet were icy. The entire car was chilled.

We bundled ourselves in beach towels from our suitcases. I changed my socks, but my feet were still frozen. I couldn’t feel my toes.

“Just keep moving them!” my wife begged.

When I began to doze off, she pleaded that I stay awake.

It was approaching 4 a.m. We had been stuck for more than three hours.

—-

My wife cried for help that wasn’t coming.

This was our third 911 call, and she was breaking. “We’ll do our best to help you,” the dispatcher told her.

Their best wasn’t good enough. Through tears, my wife explained our situation.

The tow truck wasn’t coming, she said. Our two previous 911 calls for help were not fulfilled, she shrieked. We had no other options, she pleaded.

We were desperate. Cold. Hungry. Dazed by exhaustion. My wife feared for her life. Even I was beginning to lose hope.

Even worse, routine bodily functions finally began to hit us. We teamed to fill bottles and a Cracker Barrel gift shop bag that had luckily been left in the car.

I couldn’t move my toes anymore. They were frosted over. It felt like I would never be able to move them again.

My wife sobbed again after her mother called and left a voicemail on her cellphone. “I hope you’re doing OK,” her mom said. “We love you.”

I hadn’t spoken to my dad since 1 a.m., when I assured him a tow truck was on its way. For all he knew, we were safe and sound in a hotel somewhere.

Dawn was fast approaching. My wife had pleaded over again for me to call my parents, to let them know we were still in the car.

I didn’t want to wake them. Most of all, I didn’t want to scare them.

As the first hint of daylight arrived, I finally gave in.

—

Off in the distance, a man shoveled. The snow had let up slightly and rays of sun from above the clouds illuminated the surroundings just enough for me to spot him.

I was behind our vehicle, furiously trying to remove snow from around the bumper and tail pipe so we could start the car again.

The snow was piled up above my waist. I could barely push my way out the car door. I struggled to merely trudge around the car.

My dad couldn’t believe we had spent the night stuck, in the car. When I phoned, he directed me to exit the car and clear the tail pipe.

Then, the man came into vision. I could see him shoveling near a large building 50 yards away. I frantically tripped my way through the hills of snow toward him. Hungry, exhausted, freezing, I prayed I would make it to him before he vanished.

“Hi,” I calmly said as I approached. “Do you mind if we come in for a few minutes to get warm? …. We’ve been in the car all night.”

“Sure,” he answered, shocked at our plight. With that I trudged back to retrieve my wife.

It was 7 a.m., and we would be warm soon. For how long, we didn’t know.

—

We found out that we weren’t the only ones stranded.

The shoveling man, Tony, welcomed us into a building that was buzzing with a dozen overnight workers. The mountains of snow had trapped them there.

An energetic man of Hispanic origin offered us coffee. We basked in the warmth of the building. We were grateful to be safe and out of the cold.

I sipped coffee and nibbled on a pop tart from the vending machine. My toes began to thaw. Slowly, I could move them again.

We sat at a table with a middle-aged woman. She made us feel welcome. We were at the corporate office and factory of Mayer Brothers, she explained, a company that produced juices and apple cider and bottled and packaged spring water.

The other stranded workers were young men of various races and nationalities. They spoke many different languages. There was a giant of a man from Africa. One from the Middle East who every so often lowered to his knees to pray. A small Asian man with a bubbly personality.

What had they gotten themselves into?

Us, we felt lucky. We would soon find out just how fortunate we were.

—

Morning became afternoon. Snow continued to fall angrily.

The Sorento was now engulfed, barely visible from our view standing at the building’s entrance (depicted in the video below). We weren’t going anywhere.

During the phone call with my dad, he had promised we would be free from the clutches of the heaps of snow soon. He said would put a call into my uncle, who lived 10 miles to the north in the suburb of Williamsville.

At my uncle’s home less than a foot of snow had fallen. Buffalo and its northern suburbs had somehow escaped the brunt of the storm.

Still, my uncle’s attempts at reaching us were continually met with resistance. Transit Road, like many of the main arteries south of Buffalo, had been closed by authorities.

One stranded worker attempted to walk to a nearby supermarket. The whipping winds and heavy snow barely allowed him to advance to the road before he forfeited to the elements.

A group of workers packed into a mini-van with the idea of making it home. Less than a half mile down the road the vehicle was stopped by the snow. They dug out and returned.

There were no alternatives. We all would spend the night in the factory.

For us, that was far better than spending another night in the car.

—

When we eventually made it home to Olean, we penned a heartfelt thank you to the Mayer Brothers owner and his son. We signed it, “Honeymooners”. That was the moniker we affectionately become known as to people of Mayer Brothers.

They didn’t have to let us in. They didn’t have to let us stay. They didn’t have to embrace us.

They gave us a warm place out of the cold. They let us sleep there. They even fed us.

The owner’s son, by way of a snowmobile, supplied those stranded at the factory with loaves of bread, peanut butter, jelly, and Hershey’s bars. My wife tried to pay him. He emphatically declined. The outpouring of gratitude brought her to tears.

When night came, the workers helped us lay down cardboard boxes to sleep on. We wrapped ourselves in beach towels and a blanket from the car. I used my windbreaker and another towel as a pillow.

We were safe. That was all that mattered.

We will always remember how we were treated with kindness and compassion in our time of distress. We will remember it most when we are given the opportunity to help others in need.

We later learned that the massive snow storm claimed at least a dozen lives, including one man who was buried alive in the snow. Others were trapped in their vehicles for days.

We were the lucky ones.

It was almost midnight and the longest day of our lives was nearly over.

—

It had stopped snowing. Finally. The sky was clear blue and towering piles of snow glistened brightly in the bright rays of sunshine.

Our vehicle, once almost completely buried, was now visible. Transit Road had been plowed clean.

I borrowed a snow shovel from inside the factory and dug out the remaining snow that surrounded the car. We were ready to go home.

The Mayer Brothers owner tracked down a sheriff to help us find a way home. He directed us on a roundabout escape route to Olean.

At 11 o’clock on a Wednesday morning, normally busy streets, were still barren. Plows and police vehicles roamed slowly over the arctic landscape. Cars everywhere were stranded and buried. A single man carried a case of cheap beer through the shadows of snow banks ascending to 9, 10 feet and higher.

The worst of Winter Storm Knife, as it became known, was over. “Knife,” Erie County Executive Mark Poloncarz said, because it cut like a knife through “the heart of Erie County.”

The storm dumped 76 inches in a matter of 24 hours – the most recorded in U.S. history over a 24-hour period. To put that amount into perspective, the average snowfall for an entire year in Buffalo is 93.6 inches.

The New York State Thruway, where hundreds of vehicles were trapped, was closed for days. So, too, were routes 400 and 219 – our usual paths home to Olean.

In other words, we hadn’t dodged the effects of the storm yet.

“You can’t go this way,” said a police officer guarding a closed road we needed to travel to Orchard Park and eventually route 219.

“But the sheriff in West Seneca said we could,” we pleaded.

We couldn’t convince the officer to let us pass. The road was closed. We had no way home.

Not knowing where to go, we ventured north to Williamsville and my uncle’s home. There, we showered for the first time in two days and determined an alternate route home with my uncle’s help.

Since we couldn’t take a direct route south through Buffalo’s suburbs, we drove east toward Rochester and then south. It took us two hours, but we were home.

It was 3 p.m. on Wednesday, November 19.

—

A year later, memories of Winter Storm Knife linger. For us, they will live on forever – a crazy twist to end our honeymoon, a story we can tell our kids and grandkids one day, a cautionary tale.

My wife is anxious about a trip to Baltimore we will be making soon. She keeps extra blankets, winter hats and gloves, and a small bucket – to pee in, of course – in her vehicle at all times.

Eight months after the storm – in the middle of summer – remnants of it had still yet to melt. Nine months following the storm, area hospitals reported a significant uptick in births — many of trapped mothers and fathers.

We’ve told our storm story many times over. Each time our audience has been left bewildered, jaws agape.

One of the last times I shared it was over the summer, while visiting a friend and his wife in suburban Cleveland. When I told them about the kindness of the factory owner and workers, my friend said he would make sure to buy their products if he ever saw Mayer Brothers packaging in the supermarket.

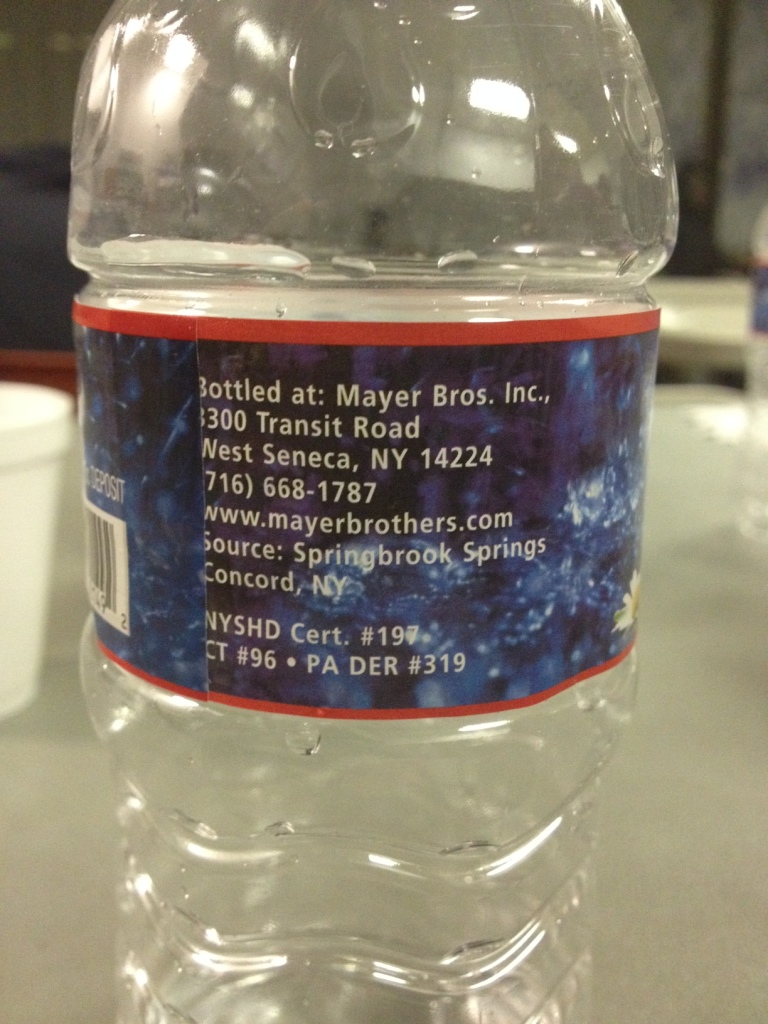

Before departing for home, my friend handed me a bottled water for the trip. I sipped it slowly as I drove. After stopping for gas, I glanced half-knowingly at the packaging on the bottle.

There it was, in simple white text across a blue background:

Bottled at Mayer Bros., Inc.

3300 Transit Road

West Seneca, NY 14224

Suddenly, memories of three days trapped in the snow came rushing back: Our 911 calls for help left unanswered. My bitter cold toes. The warm coffee. A blissful sleep on cardboard. Finally making it out.

Today, a year later, we are thankful to be home.