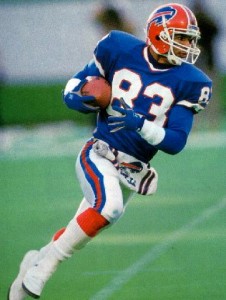

Former Buffalo Bills wide receiver Andre Reed has been a Pro Football Hall of Fame finalist since 2007.

Andre Reed belongs in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Cris Carter and Tim Brown probably do too.

Each of the three is again finalists for selection on Feb. 2. Reed has been a finalist since 2007, Carter since 2008 and Brown since 2010. Each again will cause divisive debate among the voters.

Each deserves to be enshrined. With Terrell Owens, Marvin Harrison and Randy Moss coming to the ballot soon, the time is now – or it may never come.

Since Reed is a personal favorite, he will be the main focus of this post.

Let’s start with the bare bones numbers. When Reed retired in 2000 – with the NFL still transitioning to a passing-driven game – he ranked third in career receptions (951), fifth in receiving yards (13,198) and sixth in receiving touchdowns (87). Currently, Reed ranks 11th in receptions and 12th in yards and touchdowns. Each of the 10 players with more receptions than Reed retired after him.

Reed was a seven-time Prow Bowl selection and was voted a Pro Bowl starter four times. He also played in four Super Bowls and was part of 11 playoff teams over a 16-year NFL career (1985-2000) that finished with a nondescript season in Washington.

Now let’s compare Reed to two wide receiver contemporaries who are enshrined in Canton. The careers of Reed and Art Monk overlapped for 11 seasons. The careers of James Lofton and Reed overlapped for nine seasons. By all major statistical measures, Reed had a better career than Monk, who played from 1980-95. Compared to Lofton, Reed finished with more catches and touchdowns, while Lofton, who played from 1978-1993, had more receiving yards and a better yards per catch average. Monk made three Pro Bowls, Lofton made nine.

| Player |

Games |

Catches |

Yards |

YPC |

TDs |

| Reed |

234 |

951 |

13,198 |

13.9 |

87 |

| Monk |

224 |

940 |

12,721 |

13.5 |

68 |

| Lofton |

233 |

764 |

14,004 |

18.3 |

75 |

One can reason that Monk’s edge over Reed is in Super Bowl titles – two more than Reed. Lofton, meanwhile, stands as one of the great deep threats of the modern era, in addition to playing on three Super Bowl teams while a teammate of Reed’s in Buffalo. Lofton was also fortunate to hit the ballot in the early 2000’s, before receiving numbers really began to pop in the NFL.

As for Reed, he was a key cog for one of football’s most productive offenses ever and fearlessly worked the middle of the field – perhaps with more savvy and guile than any receiver in NFL history – at a time when defensive backs were given much more freedom to harass wideouts. Yet, Reed was not merely a possession receiver. Evidenced by his nearly 14 yards per reception, he always posed the threat of turning a short pass into a long touchdown.

So what exactly distinguishes Monk and Lofton from Reed in the minds of the hall voters?

The Pro Football Hall of Fame includes 21 receivers from the modern NFL (since 1950). Broken into eras, seven of those receivers played in the ’50s and/or ’60s, six had careers that bridged the ’60s and ’70s, five had careers that bridged the ’70s and ’80s and the last three played in the ’80s and ’90s.

In other words, the ’80s and ’90s group – which includes Monk, Jerry Rice and Michael Irvin – is underrepresented compared to those from the ’50s to ’70s-’80s. But why?

I have two theories.

First, the numbers of Reed, Carter and Brown have been cheapened by today’s NFL. Teams now use short passes as an extension and substitute for running the ball. Additionally, rules are geared toward aerial football. Quarterbacks are throwing more and completing a greater percentage of their passes. And receivers are catching more balls, gaining more yards and scoring more touchdowns.

Over the course of Reed’s career, the game changed from one dominated by three-yards-and-a-cloud-of-dust offenses to those that found greater success employing five-yard-outs, swing passes, wide receiver screens and the like. For example, Reed caught 57 passes in 1987, which ranked eighth in the NFL that season. By 1994, when Reed registered a career-best 90 receptions, that amount was only good for sixth in the league. Fifty-seven receptions in 2012 would have tied Reed for 51st in the NFL with Philadelphia tight end Brent Celek.

When comparing the last four NFL seasons (2009-2012) to Buffalo’s four Super Bowl seasons (1990-1993), it was found that today’s teams complete about three more passes a game than those of 20 years ago (20.6 to 17.7). While that may not seem like a big difference, think of how many more catches, yards and touchdowns Reed – over a 234-game career – might have achieved with the opportunity for three more receptions a game.

Still, I’m under the impression that hall voters get caught up in comparing the stats of Reed, Carter and Brown to those of Moss, Owens and Harrison – when they instead should be assessing their accomplishments relative to era.

I also wonder if hall voters hold a false perception of the Bills’ no-huddle K-Gun offense of the Super Bowl years as one that tossed the ball all over the stadium. Even though the Bills moved up and down the field quickly, they ran the ball more than passed it, and Hall of Fame running back Thurman Thomas was the offense’s primary weapon as both a runner and receiver. During the Bills’ four Super Bowl seasons, they averaged 486.8 passing attempts compared to 509.5 rushes per season.

My second theory is that Reed, Carter and Brown are taking votes from one another. Just as it is difficult to differentiate the career accomplishments of Reed, Monk and Lofton, it is the same for Reed, Carter and Brown. It’s unfortunate that the three have been on the ballot together.

| Player |

Games |

Catches |

Yards |

YPC |

TDs |

| Reed |

234 |

951 |

13,198 |

13.9 |

87 |

| Carter |

234 |

1,101 |

13,899 |

12.6 |

130 |

| Brown |

255 |

1,094 |

14,934 |

13.7 |

100 |

Both Carter and Brown – whose NFL careers began two and three years after Reed’s and benefited from playing deeper into the 2000’s – have more receptions, receiving yards, receiving touchdowns and Pro Bowls than Reed, but Reed’s postseason numbers are by far superior. Among all-time playoff leaders, Reed ranks fifth in receptions (85) and receiving yards (1,229), is tied for seventh in receiving touchdowns (9) and is eighth in games started (21). Carter and Brown fail to crack the top 10 in any of those categories.

In Super Bowl history, Reed ranks second to Jerry Rice in receptions (27) and third to Rice and Lynn Swann in receiving yards (323). Carter never played in a Super Bowl. Brown played in one during the twilight of his career.

But the debate isn’t between Reed and/or Carter and Brown. They all deserve to be fitted for one of those snazzy yellow Hall of Fame jackets soon. Unfortunately, circumstances my dictate otherwise.

Andre Reed At a Glance

Playing Height: 6-foot-2

Playing Weight: 190 pounds

Born: Jan. 29, 1964 in Allentown, Pa.

College: Kutztown University (Pa.)

Drafted: Fourth Round (86th overall) in 1985 by the Buffalo Bills.

Interesting Fact: Reed was a high school quarterback at Allentown’s Dieruff High.

On Twitter: @Andre_Reed83